| Beyond Kitsch  The Highwaymen: Florida's African-American Landscape Painters The Highwaymen: Florida's African-American Landscape Painters

By Gary Monroe

University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 150 pages, 63 color photos, 2001. ISBN 0-8130-2281-9

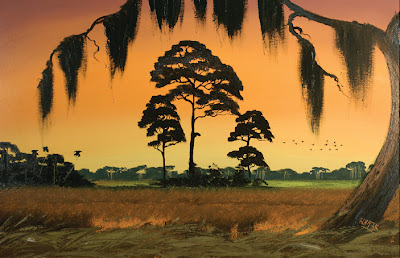

As inappropriate as the vernacular label may be when, as seems increasingly popular, it is applied to artists whose work has little visible antecedents in either the academic art or popular/folk traditions, it may be exactly to the point when considering the Highwaymen of Florida. The members of this group of black artists who became active in the '50s had no formal training and were not part of the conventional art world. But rather than being self-taught individualists, techniques and subjects were taught and shared within their group and they were heavily influenced by the example and direction of a trained artist. While there was nothing folk about their efforts, their main topic -- Florida's exotic beauty -- was certainly a focus of everyday popular taste. In fact, what makes this work vernacular is not just the artists' style, technique or imagery, but the market for which they created: not connoisseurs but ordinary people seeking a little original beauty to decorate their living rooms. The Highwaymen's expression drew on a visual language shared with their audience. "The Highwaymen's work became a popular representation of how Floridians wanted to see themselves and how they wanted others to see the state," writes art professor and photographer Gary Monroe in The Highwaymen. Because it so happens that the common language with which the Highwaymen worked was, to a great extent, the vernacular of kitsch, these paintings can challenge easy notions of artistic quality. The palm trees, exotic birds, swamps and other stock images are both inevitable in Florida landscapes and inevitably kitschy, and many of the original buyers no doubt found the paintings appealing strictly on that level. The Highwaymen could also have found a later following among kitsch collectors, whatever the actual quality of their work and whatever their story.

Monroe makes a strong case for the personal qualities of this thoroughly commercial work, while still acknowledging its strong affinity with kitsch. At first glance the work may look like Holiday Inn art show material but it's not, even if many of these artists cranked it out as fast as they could, sometimes selling their pictures before the paint had dried. They transcend their often-clichéd subject matter with creative energy. The Highwaymen as a group represented a more or less loose association of 26 men and one woman, mostly from the Ft. Pierce, Florida, area. They sold their work, an estimated 50,000 or more paintings, from the roadside or in building lobbies for $25 or so a canvas. And they worked fast. Monroe points out that the Highwaymen typically did not draw their scenes first -- they rendered with paints. Alfred Hair, one of the group's leaders, "never aspired to be the best artist, just the fastest," according to Monroe. According to a colleague, Hair worked out so he could paint faster. And he sometimes painted up to 20 pictures at a time, using assistants to put paint on the boards for him to spread and detail. This focus on speed introduced a significant element of chance into his landscapes, since he clearly did not carefully plan out his pictures. It also resulted, Monroe says, in an intuitive approach that turned what might have been plain kitsch into something unconventional. "Let your mind wander," Monroe quotes Hair as saying, noting that Hair worked from memory, without a sketchpad or photos. "A pureness and spiritedness came through in the early works as the artists lost themselves in the physical act of painting rapidly," Monroe writes. Still, although Monroe emphasizes Hair's love of painting, the point of this efficient approach was also to sell more paintings, which for these mostly working-class artists represented financial opportunity and escape from more conventional life choices. It was the promise of that escape that drew many of these non-would-be artists into learning to create, inspired by the examples of friends or relatives. Monroe describes them sometimes working in what only can be called painting bees, where they would set up in a backyard, critiquing each other's efforts as they painted in a party atmosphere. Should the thoroughly commercial, aesthetically casual motivation of these artists affect how their work is appraised? At the very least, their lack of formal training and their working methods led their art to diverge from that of A.E. Backus, the trained white painter who served as their inspiration and mentor. In the kind of turnabout that has annoyed any number of trained artists, the Highwaymen's work gained far wider distribution (and fame) than Backus'. In this case, though, Monroe says, Backus was "wonderfully supportive of the young black painters, and they idolized him."  This book reveals a body of work that conveys a definite feeling of time and place, as well as personal variances that become increasingly visible as you examine the selection of pictures. The colors are the most easily striking elements, but other qualities come through. They range from pictures of almost-schematic simplicity to nuanced views showing a sensitivity reminiscent of old Chinese landscapes, which are another example of highly conventionalized views of nature. Indeed, reminiscent of those landscapes, these pictures sometimes capture a monumentality not always evident in the real Florida. This book reveals a body of work that conveys a definite feeling of time and place, as well as personal variances that become increasingly visible as you examine the selection of pictures. The colors are the most easily striking elements, but other qualities come through. They range from pictures of almost-schematic simplicity to nuanced views showing a sensitivity reminiscent of old Chinese landscapes, which are another example of highly conventionalized views of nature. Indeed, reminiscent of those landscapes, these pictures sometimes capture a monumentality not always evident in the real Florida.

Ultimately, a big part of what makes the Highwaymen story interesting is that this group created a body of serious art work that was available to people with ordinary budgets and ordinary tastes in art, people whose exposure to canonistic art would have been limited to an occasional museum visit or Christmas card reproduction, if that. That makes this material far more vernacular than much of the work currently being slapped with that label - work whose uniqueness and lack of mass accessibility makes a label like "outsider" seem far more appropriate.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment